Supreme Court Delivers Split Verdict on Invocation of Doctrine of ‘Legitimate Expectation’

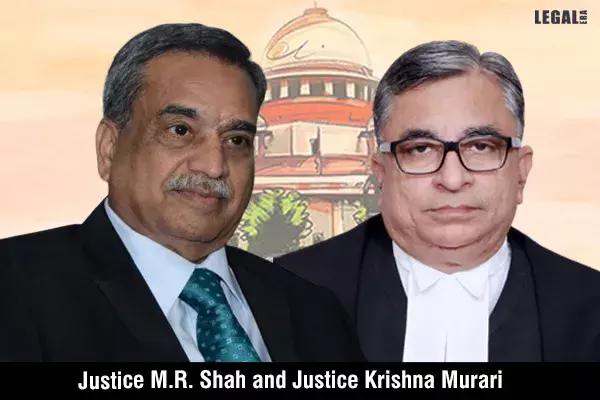

The Supreme Court coram comprising of Justices M.R. Shah and Krishna Murari while deciding a batch of appeals delivered;

Supreme Court Delivers Split Verdict on Invocation of Doctrine of ‘Legitimate Expectation’

The Supreme Court coram comprising of Justices M.R. Shah and Krishna Murari while deciding a batch of appeals delivered a split verdict regarding the question of tax exemption based on the Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation.

The brief background of the case was that certain amendments were introduced to the West Bengal Finance Act, 2001, Section 2(17) of the 1994 Act in the year 2001, and the term “blending of tea” was omitted from the definition of “manufacture” provided under Section 2(17).

The appellant i.e., a company engaged in the business of manufacturing blended tea enjoyed the benefit of exemption from payment of sales tax under Section 39 of the 1994 Act for a period of two years but then was excluded from availing the said exemption once Section 2(17) was amended.

As per the provisions of the 1999 Scheme, the new industrial units which were established after complying with all the requirements provided under the 1999 Scheme were given an exemption from payment of sales tax for a specified period upon the purchase of raw materials required for carrying the manufacturing activity in said units. Consequently, the exemption from payment of sales tax, which was granted to the appellants came to be stopped and even the eligibility certificate was required to be modified and such an order was challenged before the Tribunal first and thereafter before the High Court.

On behalf of the appellants, it was contended that as prior to 1 August, 2001, the appellants were availing the benefit of sales tax exemption, the said right could not have been taken away by virtue of amendment to section 2(17) of the Act, 1994 on the ground of legitimate expectation as well as by promissory estoppel.

The following were the two issues before the Apex Court:

1. Whether the appellants have a vested right in claiming exemption from payment of sales tax under the Act, since the vested right was accrued upon the appellants before the amendment was made under Section 2(170) of the Act?

2. Whether the doctrine of legitimate expectation is applicable in the present case since the appellants had set up their industrial units on the basis of the allurement of a tax holiday granted by the Government?

Justice Shah observed that, as per the settled position of law, nobody can claim the exemption as a matter of right. The exemption is always on the fulfilment of the conditions for availing the exemption and the same can be withdrawn by the State.

It was held by Justice Shah that the amendment to section 2(17) of the Act, 1994 which excluded tea blending from the definition of manufacture, meant that the appellants no longer qualified as manufacturers. Therefore, they were no longer entitled to the exemption from payment of sales tax which was available only to manufacturers engaged in tea blending.

“There cannot be any promissory estoppel against the statute as per the settled position of law. As rightly observed and held by the High Court, this is not a case of vested right but a case of existing right, which can be varied or modified and/or withdrawn,” said Justice Shah.

Justice Shah further noted that as per Section 39 of the Act, 1994, which pertains to the exemption from payment of sales tax, the condition for eligibility is that the dealer must be engaged in manufacturing. Therefore, the definition of manufacture is crucial in determining the applicability of the exemption. If a dealer ceases to be a manufacturer, they would not be entitled to the benefit of exemption under Section 39.

With the above observations, Justice Shah dismissed the appeals.

While Justice Shah and Justice Murari agreed that the appellants did not have a vested right to claim exemption from payment of sales tax under the Act, they had a dissenting opinion on the application of the doctrine of legitimate expectation.

Justice Murari disagreed with Justice Shah’s view on the doctrine of legitimate expectation and expressed a different perspective on the matter.

According to him, holding that public interest is supreme, he referred the case of MRF Ltd. Kottayam vs. Assistant Commissioner Sales Tax & others. (2006) wherein it has been held that legitimate expectation, as a ground for challenge, can be done away with in circumstances wherein it has been demonstrated by the public authority that the withdrawal of the said expectation has been done on grounds of public interest.

Justice Murari further remarked that, “The doctrine of promissory estoppel and the doctrine of legitimate expectation, while they share a common root and a similar theme, by way of going through the rigours of common law, have developed into two distinct doctrines. The doctrine of promissory estoppel is a remedy in private law; however, the doctrine of legitimate expectation is a remedy in public law, and as stated above, is rooted in Article 14 of the Constitution of India.”

He observed that the legitimate expectation created by the competent authority, promising the appellants a tax holiday for their tea blending activities, was broken when a subsequent amendment removed tea blending from the definition of manufacture. This amendment revoked the appellants' legitimate expectation and deprived them of the promised tax benefits. The appellants were lured into taking specific actions based on this reasonable expectation, only to suffer losses when their entitlement was taken away without any recourse.

Justice Murari was further of the considered view, that the subsequent amendment, which removed ‘tea blending’ from the definition of manufacture, lacked appropriate justification from the government. The government failed to provide a valid reason for enacting the amendment or consider the impact on the affected party.

While allowing the appeal, he concluded that the doctrine of legitimate expectation is a facet of Article 14, and is essential to maintain the rule of law and that such a doctrine, which ensures predictability in the application of the law, in its very essence, fights against the corrosion of the rule of law, and prevents arbitrary state action.

Advocate Kavita Jha appeared for the appellants while Advocate Madhumita Bhattacharjee appeared for the respondents.